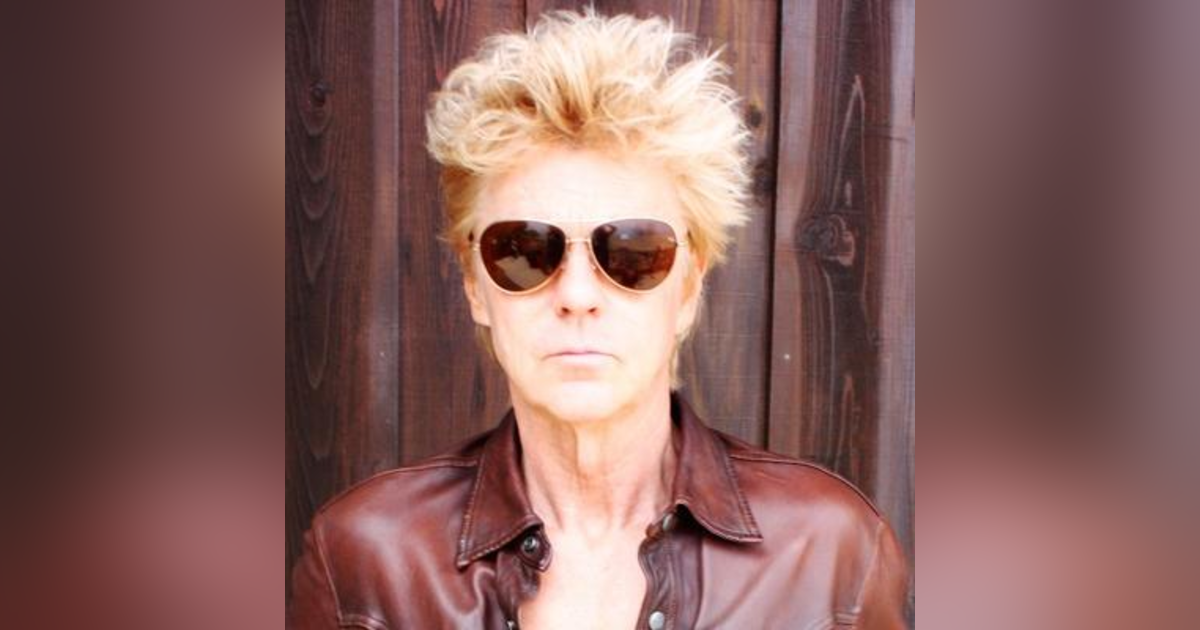

Nick Turner

Nick Turner, Co-Founder of Google DEMAND joins host Lawrence Peryer to talk about his journey from playing in bands such as Lords of the New Church and the Barracudas to technology innovator.

Nick Turner, Co-Founder of Google DEMAND joins host Lawrence Peryer to talk about his journey from playing in bands such as Lords of the New Church and the Barracudas to becoming a technology innovator and entrepreneur.

They discuss his experiences working in artist management, streaming the first live concert on the internet, building early artist websites and now democratizing data for the music business at Google.

DEMAND is Google's new data analytics platform for live music industry professionals, from artists to venue managers to promoters. Nick's team layered in data from YouTube and Google Play with historical and current pricing for events to provide a deeper look into the live music market for more than 19,000 artists.

Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Lawrence Peryer: So tell me, how do we refer to you? What is your title?

Nick Turner: My title currently is Founder in Residence at Google’s Area 120 and Co‑founder of a product called Demand, but Google’s Area 120 is sort of the incubational lab for Google and I was brought in from the outside to look at the live events industry.

LP: Excellent; all right, so I would like to talk about all of the interesting things that you guys are doing over there but I want to provide maybe a couple of decades of context on that, if you don’t mind.

NT: Okay; a couple of decades of context, okay.

LP: Well, given that you’re only a couple of decades old it should go by pretty fast.

NT: Very cool; okay.

LP: So where are you from? You have a strange accent.

NT: Yes, I have a very strange accent; a mid‑Atlantic rock ’n roll accent I’m told. Yeah; so I was born in England, obviously, grew up in London. I grew up in London during the punk days, the rise of the Sex Pistols, Clash, and from America obviously The Ramones, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, other bands like that. And so very early on I got terribly excited about the punk scene that was happening and realized that I could be a drummer; if they can play these three chord songs I can do that too and started playing drums and joined a band the next day, literally.

And so my background really after school was really in music and touring the world for five or six years with different bands, early days of MTV, on MTV and doing interviews with Martha Quinn and all that kind of fun stuff. Ultimately, I was in a band called Lords of the New Church which Guns N’ Roses opened for, REM opened for and then we were managed by a guy called Miles Copeland, who was the manager of The Police so we did all these festivals in Europe with The Police and U2 and all of those bands of the era.

In fact, I think U2s first ever gig in London was opening for my band, a band called The Barracudas, and then later obviously they did quite well for themselves. Yeah, so my early days was with being in bands and touring the world, which when you’re 21, 22 years old is not a bad thing to do.

LP: So the first band that I think most people would know that you played with, I would think would be the Raincoats, is that right?

NT: Well, The Raincoats; I didn’t even mention that. Yeah; that was an interesting band. Most notable because it’s Kurt Cobain’s favorite band and when I joined the band – and I was 19; 18, 19 and it was sort of the height of punk – it was actually three girls and me and then another guy joined, and then ultimately I left to do some other things and the drummer from Joe Strummer’s band, The 101ers joined so it’s one of those – and then later they made the first record and it’s seen as this sort of post‑punk art band I guess of some description.

LP: Yeah; I feel like if they’re known for anything at least state‑side it was really for being one of the first – I mean obviously this is after your time there – sort of all female art punk bands.

NT: Exactly.

LP: But I think to me what’s most interesting about that band, or a thing that’s interesting about that band is how sort of representative their sound is of what happened in the immediate aftermath of punk and the Sex Pistols. When people think punk they think of a very crude, primitive version of rock ’n roll and I think especially in England it was much more diverse.

NT: It was much more diverse, and obviously you know punk, it was obviously The Clash and The Pistols, but then Elvis Costello came up from punk and I guess The Police in some ways, when new wave came up. But from America I mean something like The Raincoats was much more influenced by Patti Smith and still obviously Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground and that kind of pre‑punk stuff, and Talking Heads and David Byrne and some of that new wavy kind of punk stuff.

LP: What was your – how did you get into music? You know, I have this image of that time period in England as sort of going from being black and white to one day it was in color, and whether some people – you know it was The Beatles where it turned into full color, some people it was Bowie on television? A lot of the through thread in the music you were a part of seemed to be American garage rock? The Standells, The Creation; can you tell me a little bit about where you came from there?

NT: Well, where I first came from was obviously growing up seeing The Beatles on TV and going, “Oh; that looks like a good job.” You know, seeing girls screaming at them at Heathrow airport; that was like, “Oh, I want to do that. That looks good.” But then after that it was Bowie, it was Roxy music, it was T‑Rex and these pictures of a band called Slade who some of you might know. And Slade were I think my second ever show; T‑Rex was my first ever show, so I came from that sort of glam rock era. And then when punk happened it was just a bolt of lightning, you know?

And to your point punk came and went pretty quickly in strictest terms of what punk rock was, although I guess it’s still here to some degree. It allowed everyone to understand that they could also be in a band and it wasn’t so hard. You didn’t have to be able to play like Emerson, Lake & Palmer or Yes or any of those kinds of prog rock bands. You could actually just start banging on something and with three chords you had a song, so that was the awakening for me, the punk rock.

And so then I was at school and there was a girl called Toyah Willcox who I met and I just started playing with her and some other people and played at school, the first ever show we ever did, and went from there. But once I started playing and playing in front of a crowd, you know it’s kind of infectious; there is not that much that’s better than playing in front of a crowd.

LP: Yeah.

NT: When they’re liking – when they’re hating you that’s something else but that’s cool. We experienced that too.

LP: Well, and I think for you guys with The Lords you were sort of known for your stage presence and your presentation, how did those kinds of things come about? How deliberate is that or is you just get four nut jobs on stage and they do what they do?

NT: Yeah; our singer had – was just rampant and sort of the rampant abandonment of a typical front man from that period, you know, and he would hang himself with his mic chord from a beam and he’d climb inside my bass drum and he’d stretch chewing gum from the mic stand to the drums and do a limbo dance and he’d dive in the crowd. I mean all the stuff that you’d expect and the live performance of it was something to behold.

The problem with The Lords it was a very inconsistent band because it was fueled by a bunch of interesting substances, so you know, on the most important night in Los Angeles where all the press were there you’d be terrible because you’d been up all night in Los Angeles doing what you do, and then the next night in Pomona you’d be amazing and there was no one there to see it except the crowd, so it was a difficult band.

I’m sure if you speak to our managers of the time, Miles Copeland, he’d just hold his head in his hand because it was destined to be a big band – and later bands like Guns N’ Roses and others who had a similar sound and a similar ethos, although arguably a singer with a great, great voice and very different sounding voice – sort of took a lot of the stuff that we’d sort of done and took it to the next level, and I guess continued to do so.

LP: Yeah; it’s really interesting the space that The Lords occupied. I don’t know if it’s easier to see with the benefit of hindsight, but sort of a bridge band between – you know you could throw The Doors in there even, which [unintelligible 00:09:00] voice and sort of his delivery, but the new wave, the pop, the punk undertone, your garage influence, it’s a fascinating band.

NT: Yeah; we met with Ray Manzarek – funny you should mention that, I just remembered this after 30 years – we met with Ray Manzarek and he wanted to produce our second record and Miles, our manager, wouldn’t let it happen. But in retrospect that was the right move; that would have been a great, great record but it didn’t happen.

LP: Yeah; at that time those bands were – they hadn’t had their second renaissance yet, right?

NT: No; not at all.

LP: One thing I wanted to run past you was over the last week or so I’ve been listening to a bunch of the music of the bands you were in, so my Spotify recommendations have been getting infiltrated by you. One of the funny things is “Summer Fun” by The Barracudas is now in a playlist Spotify made for me and I wanted to tell you the three or four artists that are on either side of that song in the playlist just to give you some sense of how Spotify thinks of The Barracudas.

NT: Yes!

LP: The three artists immediately before it are Screaming Trees, The Beastie Boys, Gin Blossoms and then there is “Summer Fun” and the immediate three songs after it are “Girlfriend” by Matthew Sweet – that’s pretty good company – “This is a Call” by the Foo Fighters and “Sound and Vision” by Bowie.

NT: Oh, well, that’s – I’m pleased about that. I was expecting you to say The Standells and all those sort of ’60s kind of garage bands and maybe a little bit of Beach Boys and Jan and Dean so that’s kind of interesting. Interestingly enough, when I was working at Live Nation later and meeting with The Jonas Brothers, because I was involved with them in their early days, and they had actually looked at “Summer Fun” to cover on their first record and decided not to go with it. What a drag because that would have – firstly, the royalties would have been rather good, and secondly – although I didn’t write it, the other guys would have benefited – but it would have been a nice resurrection for that song.

LP: So in the pre‑streaming era how do you think those young kids learned about that? I mean these songs tend – they take on a life of their own but it’s always a mystery to me how something like that happens.

NT: Yeah; one would imagine their publishers were looking for feel‑good summer songs and probably “Summer Fun” – it’s been on a lot of compilations of ’60s summer‑type songs for the beach. That probably showed up somewhere I would imagine in the pre‑streaming world.

LP: So when your time with The Lords came to an end were you washing your hands of being on that side of the stage or did you want to make another go of it? You talk a little bit about your transition from being a performer to being a business person.

NT: Yes; it was probably one of the hardest transitions of my life because having been in a rock band for five or six years and touring the world you are trained to do absolutely zero. So I went to work for Miles Copeland basically for almost nothing and said, “Look, I want to learn the business side of the industry.”

I bought my first laptop computer and sat there and pressed the on button having no training in computers at all and went from there to try and learn, firstly the business and learn the power of computing as well, so it was a very, very difficult transition. It really was because when you’re used to being in a band and told what time to eat and what time to get up and what time to play and what time to do whatever, I had to sort of reinvent myself for the first time.

And I worked with Miles for a few years and worked with Squeeze and worked with Belinda Carlisle and on the management side obviously a little bit with Sting as well doing some CD ROMS and that kind of stuff in the CD ROM era. And it was while I was doing the Sting CD ROM I actually met Paul Allen’s company and saw the internet for the first time around that time, which was probably ’94.

That was the big awakening because as twee as the sounds or – at that time I was one of the early people going around saying, “This is going to be big. The internet; this thing is going to be big,” and no one knew what it was. I was out there with Vangelis – evangelizing, sorry, evangelizing the internet and, you know, the internet at that point was used for email and there were a few text sites. I think UBL, the Ultimate Band List had just launched and I went out and did one of the earliest broadcasts by a band on the internet and I did one of the earliest music websites called Rocktropolis and just jumped into it with both feet and built websites for JVC, some of these earliest websites, and started a company.

That got sold very quickly to another company called N2K who was selling physical CDs through the internet and they went public and raised a ton of money. At that point I was now sort of in the internet and doing, I guess, some sort of pioneering work at that time working with [Arlis]. It seems like a very long time ago.

LP: It was.

NT: Yeah; I then joined a band – a band, I then joined a company called Artist Direct which was Marc Geiger’s company. Marc is now the head of music at William Morris and has had a storied career, but he had signed a new company called Artists Direct whose goal was to work with the biggest artists in the industry and put them on the internet. Do their eCommerce, connect them with fans for the first time, create email lists and all of the stuff that’s de rigor now, but at the time was still very new.

They had an agency and they had some other pieces to the pie, and ultimately a label and so that was fascinating getting to work with everyone from The Stones and Madonna and The Chile Peppers and [Beck] and The Beastie Boys and all of the bands of that time and trying to understand how the internet could be used in new and different ways. And we’d do live broadcasts and we would do chats, text chats with bands and all of that kind of stuff.

LP: Just dial back a little bit to the sort of early mid‑’90s when you had that moment that led you to be an evangelist for the internet. What was it you saw? What did it first strike you as? Was it a communications tool? Was it a commercial tool? Was it all of the above? What was the thing that first you said, oh, it’s going to change this aspect of the world?

NT: Yeah; I think I realized very, very quickly it was going to replace radio, it was going to replace TV – be replaced, but it was certainly [going to be] another channel for video and audio. It was obviously an incredible channel for information. You know, did you know that newspapers are going to go away the first time you saw it? Well, it became apparent pretty quickly that this is how you were going to get your news and how you were going to get your information.

We didn’t reckon for social media; you know social media hadn’t happened yet, You Tube hadn’t happened yet and so that was still ten years off; yeah, maybe ten years off when we started, but certainly we knew it was going to be the biggest information channel the world has ever seen. Bigger than TV and radio and newspapers combined; this is what I used to say back then and people just looked at me like I had two heads. The rise of social media obviously took it to a whole new level for good and for bad, but that was still a ways off.

LP: It’s amazing to think back to those early days and some of the first conversations with artists and the first – even the first interactions with fans. I think as an industry it had been so long since the industry had been so close to fans, never mind putting artists that close to fans and to start to understand – or to be reminded that fan is short for fanatic and what that meant and what people wanted more of and how much they craved in terms of access and availability and what they would do if you gave them the ability to interact with each other, communities that would sprout up.

I think the thing I remember about sort of the early web version of the internet was, you know, first of all how little there was. You know, having the Mosaic browser and going to a lot of university websites, or as you talked about, things like Ultimate Band List or IUMA, those early, early music websites that really weren’t much more than like directories to click on things and maybe see the lineup of a band or things like that.

But even in that crude form I have a very visceral memory of like I couldn’t wait until the next time I could sit down at the computer and see what else I could go find. It was very compelling, very early on, and that to me is what just – you know as a focus group of one made me realize, wow, if this is doing this to me and the other people I happen to stumble across who know about this, what is going to happen when this thing catches on.

NT: Yeah; I remember things like looking at the coffee pot in Cambridge University where some college professors didn’t want to have to make coffee so they put a camera on the coffee pot so they could see if the coffee pot was full, and so we would actually go and look at the coffee pot in Cambridge University to see if it was full or not.

Now, this is ridiculous now but at the time it was unbelievable that we could see this coffee pot in England, and silly things like that, you know? And then there was something called the Cool Site of the Day, which as these new sites started sprouting up, you know this one guy, this guy I met – I was actually nominated for Cool Site of the Day with Rocktropolis. We’d choose four or five sites of the day and at the end of the day they’d vote for one. And obviously, these new websites were sprouting up every day so it was fascinating to see what was being developed.

LP: Yeah.

NT: And it was around the same time obviously Yahoo started and some of these other sites that went onto bigger things, broadcast.com with Mark Cuban which he sold to Yahoo, yeah, for a lot of money. A lot of those things were just in the very starting points. Real Audio was actually providing some audio content; it was a very exciting time. There were no rules; that was the exciting time. There were no rules. It was the Wild West. No one knew what you could do or what you couldn’t do so that’s what made it so exciting I think.

LP: Yeah; I was recently – when I moved I was digging through some old just archival papers of mine. I came across an interview from – it was either late ’95 or some time in ’96 and it was with PC Magazine and they were asking me about what would happen – did consumers need secure servers in order to adopt purchasing on the internet?

And the irony was that, you know, consumers were so far ahead of big business – this was when Visa was talking about developing their own secure protocol and MasterCard was and nobody knew what to do. The banks were terrified that people were entering their credit cards onto the internet and people didn’t really care. They weren’t thinking about whether it was secure or not. What? I could buy books? I could buy CDs?

NT: That was the other – this is reminding me again, you know, I was at this company N2K and we were selling CDs on the internet and Amazon had launched and were only selling books and we could see how well they were doing with books until the day that they launched selling CDs. And we looked at it that first day and we realized we’re out of business; the company was out of business because Amazon was so good. It had a bigger range. They had such good customer service and ultimately that company, N2K merged with CD Now who was the other CD retailer, and I think ultimately they sold to BMG and then went out of business. But yeah; a different time.

LP: Yeah; so before we jet too much more forward what was Rocktropolis?

NT: Rocktropolis was a virtual rock ’n roll city in cyberspace you know, it had streets and buildings with different artists. So you had Sting’s Castle; I think Sting had just released The Ten Summoner’s Tale, so in Sting’s Castle you could go and find out all Stings tour dates and see I think rudimentary video clips. In the Morrison Hotel you could go and see Jim Morrison and The Doors who I think had just released a release of American Prayer, so it was that kind of environment.

The thing was, you know, you were using these modems and it was very graphic‑rich so you’d have to wait for the photo to load. It wasn’t the most optimal thing to see on the internet, but once it did load it was very pretty and so it got a lot of attention, a lot of press and I think Yahoo voted it one of the sites of the year or something like that. It was early days and it didn’t survive more than like three or four years before I think I moved onto something else.

LP: And so was the notion that Rocktropolis was a place where – that was the destination and you would sort of build these real estate experiences and they were promotional vehicles for whatever the label or the artist had going on? It was the model that they would sort of – they would pay you, you would monetize your traffic by building these installations?

NT: I hesitate to say there was actually a model at that time. I was doing it as a calling for fun and I was doing it because it was there. It was a terribly exciting time to actually build something and have people see it around the world. I was also building websites for other companies so it was a bit of a calling card to drive the sales of building other peoples’ websites at the time.

Ultimately, the model would have gone to advertising and, you know, you probably would have sold CDs. In fact, we were selling some CDs on the site but it was, you know, still very early days so there really wasn’t that much money to be made I don’t think.

LP: Yeah; how did you wind up in the States? What brought you over to actually live here and to work here?

NT: Oh; obviously I was in bands touring, but then in typical fashion it was a woman that brought me over to the States, a woman I actually married and had two children with. You know, growing up in London – London is a fabulous town but once you see the sunny skies of California you realize that every day you open the curtains it’s a beautiful day, you realize that there are other opportunities.

And I was commuting to do The Lords for a while because The Lords were still based in London, but ultimately The Lords was going downhill. You know substance issues and the band weren’t getting on and didn’t have a manager or record label anymore and it was time to move on. And so I moved to California, worked with Miles as I said, with some of these artists and then obviously jumped into the internet with both feet and had children and have never looked back. I’ve actually been here for longer than I lived in England; a long time.

LP: Wow; and were you always in California or did you do a stint in New York around the N2K stuff?

NT: I was always in California. I love New York to visit. I’m not sure I could actually live there, especially now. I love California. I’m very lucky; I live in Malibu now so I have a view of the ocean. I’m looking at the ocean right now so I’m very lucky, and I also am in the water most days so I’m either surfing or paddle boarding almost every day I can, so that is great for the brain and the mind and the body and just to get out in the water every day is a wonderful thing.

LP: You’ve probably added 20 years to your life expectancy just by choosing to live in Malibu.

NT: I think so; I think so. I think living in New York or a city where you’re fighting the crowds every day would be a different experience, yeah.

LP: So you go to Artists Direct, you’re working with a visionary like Geiger, what are you doing there for Artists Direct?

NT: So what we’re doing is signing artists to the vision and then managing the creative for them. So we’re building their websites, we’re building their eCommerce stores, we’re sending out emails. I had a team of ten or 12 folks, many of whom have graduated onto other positions in the industry, who were sort of their customer service, their artist relations people. I think they were called channel managers at the time, and it was just a great education in how the industry works and how we could change the industry.

What happened originally was that the labels saw us taking over their artists and wanted to sue us, and then ultimately decided to invest in the company. You know, we went public and it was kind of a difficult time because it was just at the time that the internet bubble was pricked. In fact, we could have been the needle that pricked the internet bubble. It was a difficult time.

And then we stayed on there, we had a label for a while and then 911 happened; I mean all these things happened, which sort of came against us. And then I stayed on actually at Artists Direct for a little period longer and sort of ran this ad network that we created, and actually created a big ad network in music.

But ultimately it was time to leave and I moved on from there and went to work at Music Today, Coran Capshaw’s company literally a week or two before it got bought by Live Nation, so then I found myself at Live Nation working with Music Today and then working with you at Ultrastar, still signing artists to do eCommerce and to do all of those kinds of things, but working more with the Live Nation folks and working with artist like The Jonas Brothers and I think Jay‑Z and some others for a period of time.

And that was, of course, also just at the period that Live Nation and Ticketmaster merged so again an odd timing where things are changing beneath you. And although I thought we had a very powerful alliance in what we were doing with Music Today and Ultrastar at Live Nation, ultimately I’m not sure they thought that so that sort of dissipated pretty quickly unfortunately.

LP: So the first, say, 15 years or so of your life in sort of the internet business or the entertainment internet business was really in – it sort of paralleled the interest in the things I was involved with in terms of connecting artists and fans. Like broadly speaking, yes, there was eCommerce; yes, there was ticketing, there was content delivery but the sort of theme was how do we bring artists and fans closer together?

NT: That’s exactly right.

LP: Build the relationship; if we’re lucky monetize the relationship, figure it out.

NT: Well, do the earliest digital fan clubs, bundling tickets with records; I mean all of those early things that both you and I would were doing. It was ultimately connecting others and fans in a way that hadn’t been done before, removing the middleman wherever possible. Labels are obviously still important but not in the same way as they once were.

So now you see artists who obviously achieve incredible success using labels in slightly different ways, like connecting with their fans much earlier in the process. Artists never had to be marketers; now they have to be marketers and write emails and make videos. All the things that artists never did before that other people did for them; the artists are now doing themselves.

LP: Do you think your music career would have been different had you emerged in this era? Would you have had an aptitude for it or was your head not – you know how do you think you – if you could have just time‑shifted into the different era how would you have dealt with it?

NT: Well, I mean knowing what I know now and going back knowing that, you obviously would have cared about your fans in a much bigger way. You would have developed better relationships with them, you had email lists and social media, none of which we ever had. You would show up at a club, you played to 1,000 people, 2,000 people, whatever it was and there would never, ever be a connection.

You know you might get a phone number from a girl, that’s probably the extent of it, so you could never identify them. The ability to identify your fans now and reach out to them in proactive ways, we could never have dreamt of that. The artists that do that well will have long, long careers, right, forever, even if they’re making bad records and lose their labels they’ll still have fans that they can connect with and who hopefully will show up to see them on a rainy Tuesday night in Chicago.

When you don’t have that, once you don’t have a label – or back in the past when you don’t have a label you can’t really tour very much because you don’t have the support. You only had press or radio; once you don’t have that you don’t have anything so it was a different world.

LP: I think one of the things that’s very interesting about this space is that, you know, it’s certainly all become so much more mainstreamed or just common practice. You know to your point, you have a relationship with your fan base, you know how to rally them, you know how to reach them potentially long before you’re signed. In fact, that may be why you get signed now because someone has got an A&R tool that says, oh, this artist has pockets of demand that they’ve aggregated on social media or what have you.

But in the early days when we were all kind of chasing either the hit makers of the times, you know there in the mid/late ’90s, early 2000s, so the end of the CD era when there were still those kinds of superstars, you know, a million week one’s and that kind of thing, while we were all going after the classic rockers, what was super‑interesting was how a lot of them got this. They understood this. If anybody had had a career of five, ten, 20, even 30 years at that point with some of the ’60s bands, they weren’t doing it the way we were doing it, but they did understand this notion of like you’ve got to give – you can’t just show up and leave.

I think artists traded on the mystique and the distance with the audience a little bit differently than they do now, but they all understood and had different comfort levels with, well, where do you let them come into your world? Some operated, you know, official pen and paper fan clubs where you could mail something in and get something back.

And I can remember even as a kid joining artists’ fan clubs and maybe sending in the check for $5, $10, whatever it was, and forgetting about it and then all of a sudden six, eight weeks later a package in the mail would come from, in my mind, the music business. The rock gods sent me mail. I don’t know how I thought it was happening. I don’t know if I even thought about is there an infrastructure for this, is it a guy in the office, all I knew was the Rolling Stones were sending me a package.

The magic of that was super‑powerful as a young music fan and what I hope hasn’t been lost now that it’s so easy to send an email and so easy to communicate over social media, is that special feeling of like rock ’n roll is talking to me.

NT: You know it has been lost to some degree. That said, it’s still exciting if you can meet your rock star icon, if you can be in the front row or in the first few rows, there is still that; there is still some magic there but it’s not the same as getting a package in the mail and that unexpected pleasure from your favorite artist. That was a pretty exciting time.

LP: I do have to say one thing – if I would feel like those of us who were there for those first ten or 15 years of this emerging online, one thing that is a not‑often discussed part of the legacy of that time, is truly how much closer fans can get to fans – or artists can get to fans and fans can get to artists. Before that, the idea that you could go to a meet and greet and meet Sting or The Chili Peppers or whomever the artist is that’s doing these VIP packages and travel packages and fan club contests, those things were so much more limited. Maybe a radio station thing, maybe if you worked at the local Tower Records you still had to be somehow connected.

So I hate to use the term but the democratizing of access to the artist is something I feel really good about having been a part of. As a music fan I love that we’ve mainstreamed that.

NT: You know, well, the world has changed as well. With streaming taking over from CD sales and all of that and people not being able to sell a million [unintelligible 00:36:02] CDs in the first week, obviously the industry had to change. Bands 20 years ago, there is no way they would ever do a sponsorship deal; there is no way they’d ever sell meet and greets with their fans or VIP access or whatever that stuff is. There is no way they would sell platinum tickets. It would be a $50 ticket, so all of that has changed.

I think ultimately for the good, but I guess time will tell. I mean obviously there’s a lot more artists now as well than there ever were before, a lot more touring artists now as well, which I think is a good thing. Where it goes from now is anyone’s guess. There is still good music being made. There are still new artists being developed, big artists. I mean for a while once The Stones and The Eagles and all these fans go away who is going to replace them?

Well, you’re actually seeing that now. You know you’re seeing the Billie Eilish’s and the others, the Lizzo’s and the Harry Styles and some of these other artists coming up to replace some of those older artists. Whether they’ll have the same effect on music is arguable but we won’t get into that right now, but certainly people still want to go and see live music. They still want to go into arenas and stadiums and see Taylor Swift or Ed Sheeran or whoever it is and that’s a good thing; that’s a good thing generally.

LP: Yeah; one of the big eye openers for me, as sort of a counter to that argument that there is not a strong bench of arena acts, because I think it was about five or six years ago now when The Black Keys came back and launched an arena tour. I remember thinking at the time, The Black Keys are going to play arenas and it was massive.

I think there is this weird balancing act. I’ve talked to several people about this recently. Some artists get rushed into arenas too quickly and it does almost irreversible damage to their careers, and some artists take that leap right before it seems like they’re ready but they get there in a really powerful way that then establishes them as a career artist for a long time, so it’s fascinating.

You know, I think a big part of it is the artist knowing their audience, trusting themselves, but then it’s also people like the Geiger’s of the world and some of the more visionary managers out there who can see where these things can go and understand how to develop and manage that profit.

NT: So not to pitch the product I just launched, but the Demand product which I just launched out of Google’ Area 120, which is a free product for the music industry, does allow you to look and see and compare your artist to other artists, both in terms of search in You Tube, pricing and other areas.

And I think that the ability to now see that will, number one, stop a lot of the mistakes that the industry has made in the past, but also that allow an artist – I won’t go into any examples – but now an artist would say, okay, yeah, we can play an arena in Phoenix and Portland and Dallas but we’re probably better to do two theatre shows in Hartford and Miami, as an example, so you actually can buy DMA, look at this different data and pay yourself to other artists and get a better understanding of where you fit in the marketplace. There is new data that’s coming out all the time that will allow you to do that.

LP: Without the benefit of visuals while we’re sitting here talking, how are some of those things done? How does the product work?

NT: Well, I’ll give you the backstory. I was invited to join Google’s Area 120 about two years ago. They were looking at live events and ticketing and asking, you know, what I thought they should do. What I thought they should do actually was not try and do their own ticketing platform and compete with Live Nations, Ticketmaster and do all that stuff, that would be ridiculous, but to actually use the data they have, which obviously is pretty extensive. Obviously, 70 percent of ticket sales start at Google, right? Foo Fighters tickets, Foo Fighters tour, Foo Fighters, the Forum, whatever it’s going to be.

Plus, obviously we have the second biggest search engine in the world called You Tube so the combination of that data I thought would be incredibly useful as an information source for the industry, number one. Secondly, when you add in primary and secondary sales data, and we have probably day by day secondary value of a ticket and some other third party sources, and put it in a big cocktail shaker and shake it up, we thought that insights would come out of that that would develop new products, and we’ve actually launched three or four different products.

One we launched called Demand, which came out a couple of weeks ago at the Pole Star conference, which is a free product for everyone. If you go to demand.area120.com you can get it there and you can see what it is. Just register us, fill out a form and you’ll be able to play with it.

But other products that have been created out it are really sort of more for internal use at Google. We understand now by looking at the announcement of a tour we can look market by market and say the three day Google activity, post the press release going out and compare that to similar artists of a similar genre and a similar size and similar era – so if you’re googling – if you’re looking at Harry Styles then you would obviously compare him to, you know, The Jonas Brothers, Justin Bieber, Justin Timberlake, Arianna Grande, those kinds of artists, big pop artists who play arenas and you can understand how his announcement fared in comparison to those other artists, market by market.

This tells you a couple of things prior to on‑sale and prior to presales. Tell you, okay, these are the top markets, these are the underperforming markets, the markets that aren’t so hot. So prior to presales and on-sales you have the ability to change marketing, change ticket prices and do some of those things that also would ultimately save you money and be more effective in the long term.

So if you’re announcing a One Madison Square Garden show and have another one on hold, but by looking at this data you actually realize that compared to those artists that played multiple nights you’re actually looking pretty good, you can probably announce that second show or even a third show at on-sale.

This saves you marketing money and saves you other things so it makes – it provides for more efficiency for the industry, and at the top end that’s great, you know? We all want the artist to make more money and we all want the promotors at Live Nation to make more money, I guess – or maybe not – but also at the bottom end. So the data is also good for small club owners, small local promotors, smaller artists to understand what’s happening in the marketplace, which artists are doing well, which artists aren’t doing so well similar to them, and plotting their career path by following some of these other artists.

It tells you where to tour. It tells you the kinds of venues you should be in. It tells you the kind of pricing that’s in the industry so we’re hoping that it’s the great equalizer because everyone gets the same data. The promotors, the managers, the artists, the agents, the labels all get the same data, so hopefully it will solve a bunch of arguments.

We were working with a midsize promotor who had just made a deal with a big artist and put in quite a lot of money, and they asked us to see the data. This is prior to when we launched and the data clearly told us and told them that this artist was on a severe decline and hadn’t had a hit for three or four years. They realized they had overpaid for that show so hopefully it will start to stop some of those mistakes from happening and provide more transparency to the industry in general.

LP: All right; there are a few things you said there I want to – I want to ask a couple of follow‑ups about.

NT: Okay.

LP: So you said everybody would have the access to the same information?

NT: Yes.

LP: Is there a lack of symmetry right now about which stakeholders have the access to data and insights and who has the most rich access before Demand and who is going to benefit the most from Demand?

NT: Well, firstly, no one has accessed to Google and You Tube data in the way that we’re providing it, right, and the way that we’ve intuitively provided it within the this product. I mean there is Google Trends. This is a version of Google Trends that is more proprietary and it’s much more focused on tickets and entertainment and also allows you to compare artist by artist, so that’s the first thing. And obviously, the You Tube data we’re actually showing raw data reviews, so to be able to see that in this new way has never been seen before.

Secondly, on the pricing side, although Ticketmaster has their data, William Morris has their data; the industry has never really been able to see primary and secondary ticketing side by side in this way either. We haven’t gone very granularly into this, we’re not showing P1s and P2s and scaling tickets; we’re showing maximum and average so it’s a very general ticketing for dummies kind of view.

I think that’s okay because when I show this to managers they’ve really never seen this view before so, you know, a major manager of a day just put his head in his hands and said, “Oh my God, we’re giving away so much money,” off to the secondary. So how does that affect better pricing of tickets, more dynamic pricing of tickets? I mean obviously they’ve taken steps by doing platinum ticket and VIP and other things.

We’ve run a bunch of models and, you know, if the artists, promotors, agents start to price tickets better, more dynamically obviously it actually will dis-incentivize the secondary to some degree; to some degree, and does that actually make the average price of tickets go down for the consumer? The models say yes; in real life we’ll see that, but we think there will be a fairer distribution of tickets for everyone across a major show.

So we think that the artist will benefit ultimately, the industry will benefit, there will be more shows, there will be more hours playing. I’m hoping also, as I mentioned earlier, that it engenders new talent and allows new talent to flourish or new clubs to start or new local promotors to actually understand their markets better and develop new music scenes. Who knows? Who knows but that’s the hope.

LP: And what do you think, if you’ve had a chance to think about this at all, what would be three months from now, six months from now, nine months from now, if you got a piece of feedback from a stakeholder in the industry, an agent or a manager, a promotor where they said, “My use case for demand was X, Y Z and it and it made such a big impact on my business or on my thought process,” what sort of is your dream use case that you see from the industry and what would make you feel really gratified to hear it had impact on?

NT: There are a couple of things but one, we’re providing this product as a free product. The reason to do that was to get people to use it and adopt it for a period of time.

LP: Because after I love it so much I’ll actually pay for it?

NT: Potentially down the road there may be new tranches of data that we will roll out, more granular data that perhaps we will have people pay for. We haven’t determined that yet. You know, part of the reason for doing this is we believe if Demand can help raise the industry by a percentage point, a couple of percentage points, then does that benefit Google in the long term? Yeah; it does because people will obviously spend more money on advertising and so Google will actually benefit there.

Google is making near 30 year bets, you know, so if we can lift an industry and Google can be part of that lift that would be a tremendous thing. Whether we charge for some pieces of data or not is to be determined. It’s not a huge business to do that really because the industry is kind of limited so we’d much more prefer to have people spend more advertising money on Google and have Google be more top of mind amongst the industry.

You know there are other products out there. Spotify has a product, Apple has one but we believe – we hope that we’ve sort of set a new standard in providing data for the industry that will benefit us long term.

We have some other products also that we’re rolling out in the next few weeks which are more to do with live event calendars, the number of shows that are happening, both music and sports which will be rolling out in the next weeks, which will be beneficial to the music industry but also beneficial to other industries. The travel industry, transportation, hospitality, the movie industry perhaps as well, so this is just – Demand, the first product which is the stepping stone to some of these other products and those will be paid for, revenue‑driving products.

LP: A little big vague, and I understand that you probably need to be, but are those sort of under the umbrella, from the consumer point of view, of discovery or are they promotional tools for industry?

NT: More to do with discovery and the organization of data and transparency of data, that really Google is the best entity to do. So if you know which artists are coming to town or which sporting events have been announced, and you know the earliest possible date, the announcement – and that’s in a structured way – who knows, the hotel chains may change their room prices. They may choose to advertise around on-sale. It may help them to look at their supply chain.

They may not look at data and go, okay, this is the busy weekend this year where we have Paul McCartney coming to town, The Lakers, Hamilton is playing at the local theatre, all of this stuff is happening, so this is our busy weekend so we should dynamically raise prices, presumably, and probably get more bar tenders and more maids and more supplies in, versus this is the weaker weekend so, you know what, perhaps we should think about lowering our prices, do a special offer, a weekend offer or whatever it is, but doing that in a very structured way.

Right now it’s sort of anecdotal and, oh, you know, but it’s not done in a structured way, so part of what we’re trying to bring is structure to the live events industry and all of the supporting industries that surround it.

LP: That’s phenomenal. When you talked about some internal tools for Google would that be things that would allow, say, a sales team to act on some of those insights? So they could say, oh, you know what, this on‑sale, I go across the grid, there is softness in these markets, I’m going to reach out to the tour market or to the digital marketing team at Live Nation or what have you?

NT: I would say you’re exactly on the right track, yeah.

LP: Yeah.

NT: Where there are hot markets obviously where there is more demand, probably some of those advertisers should need to raise their bids, right? Where there are softer markets obviously marketing needs to be shifted into those markets, but that’s kind of what we’re talking about.

LP: Yeah; it’s advertising as value‑add. It’s amazing. So a couple of just quick things; I know we’re clocking down here – there is a little bit of a gap of time between where you left the directed consumer space and you started up with Demand. What happened in those intervening years? We could talk as specific as you want but I have more of a notional or philosophical question, which is what leads you from being so immersed in the sort of artist to fan directed consumer business, to now being so passionate about helping more of a B2B look? What is that transition? Was it impacted by what’s going on in the world or was it just your career path? I’m curious about that?

NT: It was somewhat of a career path but it was also a realization that if we could take these B2B steps, that also a lot of the data that we’re correlating can also affect the consumer. So part of what we’re looking at is how does the data that we’ve pulled together affect the consumer? So again, these other products are sort of baby steps into understanding how we might look at Google and provide some of this data back to the consumer in a way that’s more effective for them within Google.

If 70 percent of searches start on Google is there a way where we can use this data to keep people on Google for longer, as an example? You know if we can say here is the range of prices, and we have obviously machine learning capabilities to understand where the prices are trending up or trending down, is that something that we can provide to the consumer in a way that makes their buying experience better and easier and more cost effective? Maybe, down the road that’s what we’re looking at.

LP: Yeah; I think philosophically a big reason why, when presented the opportunity, I threw my lot in with [light] is that I truly believe that the companies whose organizing principles are around making things easier, better, more engaging, more exciting, less friction, for consumers when you organize your business around that notion, especially if you have a B2B offering that is driving ease of use and ease of consumption for consumers, I think that’s the sort of meta‑trend right now and I think that’s the place to be.

NT: I agree. You know, at Google it’s always about, okay, well, how does this affect the consumer? What can we do to make the consumers’ life better, so I’m hopeful that down the road some of the data that we’ve put together and some of the insights we have, can affect the consumer in a direct way.

LP: Yeah; and I think it’s also a bit of a green field because a lot of the incumbents and a lot of different spaces in and around multiple industries, not just entertainment, aren’t well equipped to have their interests aligned with what’s best for the customer because of legacy, modes of doing business or contractual obligations, mentor models or whatever, so I think it’s a great opportunity. Is there anything I didn’t cover? Anything you wanted to say or need to say?

NT: No; I don’t thinks so. The middle period from I think Vivo and Live Nation on I started a television distribution company to do on‑demand television for the internet, so creating channels for the internet, and that thought is still going. But then when I got the opportunity to join Google and build something completely new that brought me back to music, which is obviously my first love, that was an easy decision to make. And to be able to look under the hood of Google and see the kind of data that they do have and understanding general that, you know, how powerful the data is, was terribly exciting. It still excites me every day so I’m happy to be there and to build.

LP: Well, I’m glad you’re fighting the good fight on behalf of fans and on behalf of the business. It’s great to see tools and functionality that can align the interests of both of those camps because that’s how we’ll go from people going to one or two concerts or one sporting event each season, to viewing all these things as more regular parts of their lives.

And they’ll go to more clubs and theatres and arenas and stadiums and they’ll spend more money in those venues because we’ll just make it easier and we’ll make it better, and it doesn’t have to be an unpleasant experience. People come out in droves to go to live events and it’s super‑difficult. As we start to make it easier as an industry I think really great things are going to happen for everybody involved.

NT: I think so too. The power of live is still so strong and hopefully it remains that way.

LP: Well, what can you talk about in terms of the product as a recovery indicator?

NT: Obviously, I mean, like you have, we have access to all the secondary tickets, right, so we can see who’s buying tickets right now, which is nobody, versus obviously who starts to buy regionally to show the interrelations to go to events again and start buying tickets. We also can see obviously the secondary prices. And then thirdly, probably which you guys don’t have is we have the proclivity to travel. So where some people are traveling across the country for the Rolling Stones or whoever, we can actually now see their searches for travel from other [DMAs].

So if people are only searching in Seattle right now and you have a [unintelligible 0:02:30] Seattle, we can see the searches from San Francisco and LA and Chicago and other places. So that obviously is great for hotel chains, airlines, rental car companies. Any of those folks because it gives you the opportunity to understand that people are thinking about traveling again. People are buying tickets in markets they’re not in. Therefore, does that give you the visibility to think about marketing a hotel and soft opening a hotel again? So all that kind of stuff. And its obviously gonna open up regionally as it now. It’s not opening up – and obviously it may be closed again as well.

LP: Yeah. It’s interesting the way it looks like it’s going to expand and contract maybe a couple of times.

NT: Yeah. I think so.

LP: You said something that’s interesting though. We are still seeing demand. It’s been fascinating. As we started to roll out and adapt the platform into a sort of postponement tool, we’ve added a bunch of different features and functions that go just from returns to how you would apply it in a postponement scenario. And as out festivals and venue partners are allowing people to return their tickets through the Lyte platform, we are not seeing a massive drop off on the demand side. In fact, most of the return inventory is getting absorbed by waitlist demand. So the interesting thing we’re seeing is that people are still willing to put their credit card down and plan for the future. I think people are really appreciative when they have more than just the binary choice of refund my ticket or hold my ticket.

NT: Yeah.

LP: I think if you give them some flexibility and some feeling of agency about it, they’re more likely to do the thing you need them to do which is hold onto the ticket or roll it over to another event. It’s been fascinating to see the implied senses behind that.

NT: I think that’s what Ticket Master and Live Nation are counting on is that people will not want refunds. The question is are you seeing people still – well, obviously you preregistered these folks, right, with their credit cards. So obviously if tickets become available, they probably get snapped up automatically – I don’t know if [unintelligible 0:05:00]. Are people buying tickets for this year or are they buying tickets for next year?

LP: No, they’re buying tickets for this year. The festivals that have been postponed, you know, we’re working with BottleRock, Bonnaroo, Coachella, [Rockly City]. People are choosing to hold on or rollover their tickets to the rescheduled dates in greater numbers than they are asking for refunds for sure.

NT: Yeah, that doesn’t surprise me. Everyone is generally optimistic, right? They think that Coachella is gonna happen in October. Well, I mean, I hope it does obviously. But I think there’s no guarantees for any shows this year but obviously people are optimistic and they should stay that way. I’m optimistic too.

LP: Yeah, exactly. I think the big thing that this is a little bit separate than when I wear my Lyte hat is that a month ago, I was a bit more skeptical about our positive results just because I kept saying to everybody it’s early, people aren’t feeling the money pinch yet. But you know, now that we’ve gone through a credit card cycle, a month of people having to pay bills and we’re still not seeing massive rushes on return, I think it’s very encouraging. I think that people – if you wanted to go to Coachella in April, you want to go to Coachella in October because I think you count on the fact that Golden Voice is going to put on an awesome event or that C3 is going to put on an awesome Bonnaroo. So if your life circumstances permit it, you probably want to go.

NT: True.

LP: And you might put it ahead of some other things that might compete for that money. You already bought the Bonnaroo ticket, maybe you didn’t pay for your long weekend vacation this summer so you keep the Bonnaroo ticket. So that part of it is not that complicated to me. I always worry that the longer this goes on, just the harder it’s gonna be for people to hold out and not need the money.

NT: Yeah, no, I think that’s – we know that there’s a lot of people hurting right now and so we have to be optimistic that things return to normal and those 15, 20 million people get their jobs back, right, and quickly.

LP: How’s the evolution of your product offering being used? So it’s an intention indicator that you can then package to the hospitality industry or similar marketers who are looking for signs of recovery?

NT: Yeah, it’s not just signs of recovery. It’s a global database of concerts, of conferences, sporting events, of theater. Most of which obviously is not happening right now. But it adds in never before seen Google data. So we can project audience size, for sports for example, if it’s a baseball game and it’s the two biggest teams going into the playoffs, you know there’s gonna be 40, 50,000 people there versus if it’s the two worst teams at the end of the season, no chance of the playoffs, there’s gonna be 5, 6,000 people there. Right.

So we can do all that projection for concerts to theater and other things and conferences as well. So obviously we had South by Southwest and we had a bunch of the Google conferences. So you can predict all of that. You can also see a bunch of demographic information, who these people are, the age groups, the gender, the insights of what these audiences also like. Right. And then we’ve added then, you know, rather than to go along with you, start time and end time or start time and run time of these events. And then companies like Uber and Lyft will use that or we’ll see the hotel industry, airline industry will use all of that. And then we’re seeing even folks in the retail space find this data very valuable to know in a structured way across 210 DMAs, all of the events that are happening in the neighborhoods. The busiest day of the year versus the not busiest day of the year or what would they do differently in terms of pricing, in terms of supply chain, if it’s a hotel, do they need more supplies, more maids, more bartenders. All of that stuff whereas on a day its not busy, what do they have to do to get people in terms of promotions or marketing to get people into their hotels.

So we bring a lot of that kind of stuff and we were talking to a major soft drinks company who will remain nameless who said when the [Wuhan Province] went down, they lost a lot of money obviously but when it came back, they lost even more money which I thought was a fascinating anecdote because they weren’t ready, they didn’t have their supply chains in place, they weren’t marketing. They just weren’t ready for the world to reopen. So we’ve been using that anecdote with a bunch of these companies which we hope will make them smarter coming out of this crisis. So using this data will make them smarter or more efficient coming out of this crisis so that they can reclaim some of the losses much faster. So we’re talking to hundreds of different brands right now using this data. And I think it's gonna help different industries, different verticals come back. We’re hoping anyway.

LP: Wow, that’s fascinating. How is it packaged and presented to them? Do you have it productized yet? Are they able to log in and see this stuff?

NT: It’s actually available through the Google Cloud marketplace in big query which is the Google database. So they can go in there with their structured data, latitude, longitude of all their hotels or all their retail stores or whatever it is and compare it against our data and we’re getting insights from that. It’s a paid product but we’re doing trials right now in over 30 something different companies who are going and looking at the data and comparing their data sets with our data sets, looking at new insights and understanding where all of this goes.

LP: That’s amazing. Good for you guys.

NT: Yeah.

LP: So will you be coming --

NT: Was gonna say, we had to pivot a little bit. Obviously we launched a demand product for the Lyte Events industry back in February while we were building this other product called the Lyte Events Tracking, but the demand product was put in the hands of the agents, and managers and labels and other folk promoters, a lot of folks. It was being used which was wonderful to see that and it seemed to be valuable, venue-to-venue operators as well. With the arrival of Covid-19, obviously a bunch of that closed down. But what is interesting now, we’re now seeing people start to use it again. And one of the challenges for us on the demand product, because as you know, we were showing the amounts for the tours.

Question is, are the announcement tours and the activity on Google around the announcement of the tour, is that going to be markedly different from the announcement of the tour from a year ago? My assumption is yes, the search activity is going to be marketed different. In some categories, you might be less and in some categories you might be more. My assumption is that there’s going to be significant search activity around events moving forward because of the pent-up demand and everything else. So our product will have to learn very quickly in order to be able to compare the different models and to understand the different search activities on Google today and through July and hopefully things start getting announced versus, you know, three months ago.

LP: So in the past where it relied on sort of being an apples-to-apples comparison between tour cycles, there’s gonna be a giant asterisk now in the data.

NT: That’s exactly right and I’m hoping our machine learning and our AI can learn very, very quickly but it’s gonna take a little bit of time just to ram back up and understand what new normal actually means.

LP: Yeah. If I had to place a bet, I would assume you guys will figure it out.

NT: I appreciate you saying that. So we have the two products; we have the demand industry product which was the free product for the industry and then we have the Lyte events tracker which is a paid product for brands and for retail, for transportation and hospitality which we’re seeing a lot of traction around. So the combination of all that data together was pretty fascinating by having a bunch of major companies say that they’ve never seen this kind of data before, they’ve never been able to identify these audiences before the same way. So we feel good about that. We’re working incredibly hard. Obviously when we realized that we could actually show some recovery indexes around tickets and ticketing and traveling, that was helpful. So we’re providing that to a bunch of brands right now, obviously at no cost. Just to make them smarter about the way things are coming back and doing trials with them. So we hope that we’re on the path to something, something positive.

LP: Yeah, no, that sounds really great and I’m excited to help get the word out about that. Well, thanks for giving me the update. We’re gonna get this appended and add a little epilogue to our initial discussion and get this out to the world pretty quickly so that we don’t have to do yet another epilogue.

NT: Well, you know, if it doesn’t come out by June/July, I’d love to be able to say well, we have to do another addendum to this but not sure.

LP: Well, as the products keep coming, this is always a place where you can feel welcomed to come talk about it and address the industry. All right. Well, thank you.

NT: Always a pleasure.

Nick Turner

Digital Media Entrepreneur and Executive

A technology innovator and entertainment marketer since 1994 when he produced the first ever live video concert broadcast by a band on the Internet, he has wide ranging experience in the music and entertainment industries, including all aspects of online and traditional marketing, business development, sales, social media, e-commerce, content programming, online advertising and the application of new technologies that allow marketers and brands to leverage the digital economy!

His most recent three year tenure as Founder in Residence at Google's Area 120 allowed him to build innovative, entertainment and commercial products; mixing Google's proprietary data with his real world entertainment experience and contacts to bring significant value to Google, and Google's largest clients and customers.

He has spoken at numerous media and technology conferences, including at the Mashable, 'Produced By', Vidcon and Pollstar conferences.

Prior to Google, from 2012 to 2018, Turner was the Co-Founder of an OTT (On Demand Television) programming and distribution company, TV4 Entertainment, which had distribution partnerships with Hulu, Amazon, Roku, and others.

Until early 2012, he was Senior Vice President of Digital Media at Relativity Media, who produced movies including The Social Network, The Fighter, Immortals, Limitless, Mamma Mia, The 300 and others, where he oversaw a team dedicated to building sustainable online platforms, and created opportunities that redefined the way movies are marketed and distributed.

H… Read More