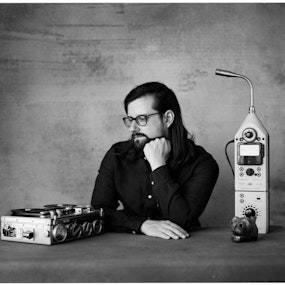

Hainbach: crafting soundscapes from forgotten relics

Experimental musician, YouTube personality, and excavator of rare, electronic sound-making artifacts — Hainbach delivers a fascinating look into his prolific musical activities.

Today, the Spotlight shines On Berlin-based electronic music composer and performer Hainbach.

I have come to view Hainbach as much an archeologist or audio specimen collector as he is a musician. While he makes beautiful music and soundscapes, they are often showcase pieces for the devices he works on, which include not only vintage and rare modular synthesizers but also tape machines, test equipment, and other industrial machinery. A particular highlight of his work is his YouTube channel, where Hainbach brings experimental music techniques and the history of electronic music to a wider audience, frequently displaying how he gets usable sounds from these forgotten devices. We have included a link to that in the show notes.

He is a fun and creative human, someone I am grateful to have spent some time with.

(all musical excerpts heard in the interview are taken from Hainbach's The One Who Runs Away Is the Ghost soundtrack)

--

Dig Deeper

• Visit Hainbach at hainbachmusik.com and on his excellent YouTube Channel

• Purchase Hainbach's music on Qobuz or Bandcamp, and listen on your favorite streaming platform

• Follow Hainbach on Patreon, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, and Twitter (X)

• Meet the German Producer Making Music With Salvaged Nuclear Lab Equipment

• Sonoscopia – Platform for Experimental Music - Porto

• Raymond Scott Electronium

• The cosmic messenger: How Karlheinz Stockhausen shaped contemporary electronic music

• The Surprising Musicality of a Telephone Line Simulator (Axel Line Simulator)

• Hainbach - Landfill Totems

• German Institute for Standardization: German Technology and DIN-Norm

• VERMONA – synth-manufacturer with a long tradition

• See the incredible and nearly forgotten Subharchord synthesizer in action

• TONTO: The 50-Year Saga of the Synth Heard on Stevie Wonder Classics

• Space Oddity: the weird history of the Soviet ANS synthesizer

• The Oramics Machine: A Relic From The Roots Of Electronic Music

• Daphne Oram – Electronic music pioneer

• The EMS Synthi 100 and ten innovative records it helped define

• AudioThing: “Made with Hainbach” Plugins

• Using a Soviet wire recorder as a ghostly space echo

• What is granular synthesis?

• A guide to Iannis Xenakis's music

• Shock (2023 movie)

• Sergio Leone's The Good, The Bad and The Ugly final duel - music by Ennio Morricone

• Why is this 90s home keyboard still so valuable?

• How Hainbach tackled 'the Dark Souls of synthesis'

--

• Did you enjoy this episode? Please share it with a friend! You can also rate Spotlight On ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ and leave a review on Apple Podcasts.

• Subscribe! Be the first to check out each new episode of Spotlight On in your podcast app of choice.

• Looking for more? Visit spotlightonpodcast.com for bonus content, web-only interviews + features, and the Spotlight On email newsletter. You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Mastodon.

• Check out Spotlight On's next live event at The Royal Room in Seattle on Saturday, June 22! More info here.

Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

(This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.)

LP: Well, thank you so much for making time. I'm so excited to speak with you.

Hainbach: Thank you. You're welcome. Thanks for having me on.

LP: You have put out an overwhelming amount of work, whether it's your actual audio recordings or your YouTube channel, not to mention the scoring work and plugins. You're just incredibly prolific. I wonder, what is that about? The sheer volume of work is amazing.

Hainbach: I find it hard to say no to interesting things. If there's something interesting that catches my attention, I'm like, "Yeah, why not?" I transitioned from one line of work into another. Pre-pandemic, I spent half the year working for theater, composing music for theater plays. Then the pandemic hit, and that job dried up like nothing. There was nothing anymore, and it was an incredibly frustrating experience. I felt helpless.

What I did then was I went home, and in a day, I recorded "Isolation Loops," which was a bunch of sounds from my studio. I said to myself, "If we are all in this together, hear some sounds, make something beautiful with that." I put them up for free or pay what you want. So many people downloaded and used those, and some people even paid for them. I was able to make up some of the lost income from that, which I hadn't expected. Then all the other things happened, like my YouTube channel. I did a lot of live streams that blew up. Instrument-making became a big thing, making all these plugins. It just went on.

Now I'm at an interesting point where live music is coming back again. I drove myself into a wall over the winter because I was touring almost every weekend. Then, I was doing all the other things that I built up. I released two plugins within three months and put out an album, and it was a lot of work. Now, my job is to make everything a bit slower. At least, I tell myself that, but it doesn't work because now things are happening. There are so many things that are put in motion that are just happening and happening. I'm not complaining. It's all good. It's just challenging to manage all these things sometimes because it's just me and my wife, who helps me with all the bookkeeping and management on the side.

The good thing is that much of this is fun. It is fun to dive into these things and explore the histories of instruments. It is fun to spend two weeks with one single instrument, exploring its depth and recording music from that. It's fun to score a movie. It's fun to make music with other people. All of these things are good, so I shouldn't complain.

LP: I love and try to live by the "why not" philosophy as well. Sometimes, my willingness to embark on a situation is undermined by my lack of capability. Still, I seldom let that stop me because even if some of those things are not fun, they're always interesting.

Hainbach: Yeah, you learn something, and that leads to another thing. Things sometimes lead to things, and I'm happy that things lead to things. At many points in my life, I felt like there were dead ends appearing, especially as a musician. A band falls after five years; another project falls after some time, and theater jobs dry up. These feelings of helplessness are horrible when you don't know what the next thing is going to be. I prefer this situation right now.

LP: As I was preparing for our time together, I have this page of notes with circles and lines, trying to figure out how to map a discussion with you because there is so much to talk about. Something that I'm very curious about is when it comes to the equipment that you have assembled, are you out scouting, or is it at a point now where you're known for this, and people are calling you constantly? Where does one come across a Soviet-era 1950s piece of electronics in this day and age?

Hainbach: Oh, there are many ways things reach me. I have alerts for things on all the sites, such as classifieds, eBay, etc. I've gotten very good at searching through things. Sometimes, I just browse for fun through the business and industrial sections, and then there is something. Now people know me, and they say, "Hey, I found this in the Netherlands" or "I found this in France. I think you should check it out." I'm like, "Okay, that's a good idea."

Sometimes, I just scroll through Reverb, and then I find something that makes me think, "Oh, I never heard of this. This sounds very interesting." If it's cheap, I buy it. If it's not cheap, I try to research it if it's anything decent. Sometimes, I get contacted by museums now. They say, "Do you want to have a look at our collection and see what's happening there? Work with our musical, mechanical instruments or something like that." It's a mixture. Things find me, but I also try to find them.

Oftentimes, these are from people, usually older men, who collect a lot of stuff, and then they pass away. Now, it's often the family that contacts me or friends of the family. I've dealt with that myself. It's hard to pass on the collections that your parents have. I just did that with my family home. I took all the things, and there were all these books because my father was a professor. It was full of books, and I was like, "Oh my God, we're never going to get rid of all those books." But then people came, four people from this reading circle, and they were just like, "Ah, I want this. I want this. I want this." I was so happy that somebody would be interested in the books.

Then, from the university, a fellow professor came and took a lot of things. That felt really, really good to know that these things go somewhere where they're appreciated. That's similar to what happened to me. They know I appreciate these things. I either use them myself, or I helped build up a studio in Portugal, in Sonoscopia, where lots of my equipment went. I connected them with this one guy who was dissolving his father's collection. They said, "I take some, and they can take some." Then they have a studio, and I have a studio. It's like that. There's often a story to these things now.

LP: Is your collection living and breathing in that pieces come in, pieces go out, or do you tend to hoard and accumulate?

Hainbach: I don't tend to hoard. That's why a whole pallet of stuff went to Sonoscopia. I didn't want stuff that I was not using, especially not in this studio. This is my main studio here, and everything must work. Everything has to work, and everything has to serve a function. It has to be on in seconds, and then I can just use it. It has to be immediate because this is also the place where, when I work with directors or other musicians, they come in. They want to try that, and it's more frustrating if it doesn't work.

I try always to have this spot ready. Then I've got another spot, which is in our gallery space. That's just for making really calm music without pressure, just two tracks on tape with a few modular things. Then, I built a studio in the cellar, which was my rehearsal studio for a live setup based on test equipment and an Electronium. This 1950s accordion is actually a vacuum tube synthesizer and sounds enormous. It was used by Stockhausen, among others. That's my live space. All these things work, and I pass on everything that I can't get to work anymore.

Some things I buy, and then I think, "I'm going to make a video." Then I just lose track of making the video. It's still in its original box sometimes because I want to film the unboxing. I'm like, "I can't try it. No, I have to find the time." My backlist is enormous, and I have so many wonderful things that I want to make a video about. That's just another problem of time, mostly. I'm not hoarding, so everything that's not usable has to go because it's not as much of a collection. I call it an 'instrumentarium.' Does that make sense in English? It's like active. All these instruments are active. You can just take them and play with them.

LP: It's interesting because I was watching one of your videos about a piece called the Axel Line Simulator.

Hainbach: Ah, yes.

LP: It was interesting because you made a comment in that piece that I think relates to what you just said, which is you talked about being sucked in by the machine. You can't just take it and play with it for a minute and walk away. Once it starts happening, like you're there, and it's the tones. You are coming and all the ways to sort of ride the wave that the machine is putting out. Part of it goes back to fun, but these sounds are just sort of warm and enveloping and never-ending and so given to exploration.

Hainbach: Yeah, and I feel like that fascination comes also from one belief that I have always had, which is that all the music is out there. It's like it's all there. I just need to find it. I constantly try to find things in things. I got this from the singer of my very first band because I was giving her chords and something, and then she would come up with the melody. I was like, "Where do you find the melody?" She said, "It's just there. It's already there." I asked, "Where is it?" She replied, "In the overtones overlapping, there are all the melodies in there."

So I started searching for these things that were already there. I found two very interesting ways to find these. One is trying to break an instrument or rather go to its borders, where this thing starts not to do what it's supposed to. Oftentimes, beautiful things happen there.

I've had so many experiences like that. I had one Moog phaser but not a Moogerfooger. It's a filter bank, the last of these big pedals that Bob Moog designed. I plugged it into some test equipment, and that voltage was way too high for it. The thing just blew open, but it sang. It was like, "Wonderful overtures! Oh my God, I found the hidden mode!" It turns out that the hidden mode was the thing dying. The microcontroller just fried, so the thing was dead after, but it sounded glorious for a moment.

Same as on my record Landfall Totems. where I made a piece called "Funktionsverlust," "Loss of Function." It was made from three statues that I built from test equipment. Usually, these things just go "beep" in a straight line, but one of them started to go "dim, dim, dim, dim, dim," and it was wonderful absolutely glorious tones. I was like, "I need to record this." I recorded the track and felt good. I went out, had a coffee, and came back after five minutes, and then there was a smell, a smell of burnt electronics and a little bit of smoke still in the corner. That was the dying song, the swan song of this oscillator, because it just broke. That's why it sounded so good. The components were basically dying, and that instrument sounded really good. It was actually breaking as I recorded it, and I caught that. That piece is an important piece for me.

So breaking things, and that can be with tape, finding the edges of where the medium, where the instrument, or where the medium, be it tape or digital, starts to show how it's made. It loses everything it tries to be. It just becomes what it is.

The other way I try to do this is by using lots of filters, such as bandpass filters, which are just really narrow filters that will select just a tiny band of the audio spectrum. Then, I can listen and sweep through things. What I find there feels a bit like science, especially because working with these things that have all these ginormous dials and were state-of-the-art in 1957 and cost as much as a house, now it's just garbage, a dump. But to find what you can hear is beautiful, and that's not only because you find things in the noise, in the frequencies. You hear the instrument itself because every electronic instrument and filter has its own resonant frequency. Suddenly, you're hearing the ripples around the filters singing. That's absolutely wonderful. It's a bit like the act of listening changes what is listened to.

LP: A few more questions about equipment. I'm sorry; I don't mean to spend all of our time here, but you're a unique resource for some of these answers that I have questions about. It strikes me that the ability to tap into the machines in the way that you do is facilitated by international standards for plugs, jacks, and the actual mechanical interface. Something that is so interesting to me when I watch some of the videos is that they all have the plug. I'm sure there are cases where you come across arcane, bizarre interfaces, but the idea that you could just grab a cable and plug it in is really incredible, and I can't quite name it. I would imagine you must have thousands of cables.

Hainbach: Yes, and I never have the one that I need in the moment. I was just lugging in a big old pulse generator, and I set it up there. Then I wanted to plug it in, and I realized it has a very weird three-pronged industrial power plug that's meant to seal in there, so it's watertight. I was like, "I don't have that." Okay, do I want to tear this thing apart and put this other plug in? No, I don't have time. So I didn't use that.

That's often the case. It's a question of adapters upon adapters upon adapters, which are sources of failure. It's not good to have too many adapters, but it's also very fast. Right now, many of these things are patched with laboratory cables, like banana cables, as you find in any school laboratory. It's really helpful and really easy, but it is not the best for isolating against noise. There's always crosstalk and bleed and stuff like that. When the cables pass each other, they will interact sometimes. It's not great in that regard, but it just works because it's fast, and you can do a lot quickly.

I've often thought about how to make things more, for lack of a better word, professional or standardized. Still, it's impossible even for me to decide on one standard because there are so many different connectors and so many different things. To force these things to be all this one thing doesn't really work. There are pros and cons to all of these things. I try to keep the lab aspect here, and that feels good. The lab aspect of the whole thing feels very healthy in a way that I can still, even though I have settled on a few choice pieces for this spot, I can still take this off and put in a new one instead of having everything racked up and fixed.

Standardization is an interesting question because I get so many questions about audio cables all the time. One of the biggest questions that always comes up in the Hainbach subreddit is about German DIN cable, Deutsche Industry Norm, which are the cables that are used on all these Uher tone tape machines and stuff like that, or even banana cables. These are cables that are not known to many people, and also because they're a German standard DIN, it's a bit like MIDI, but of course, then there are all these different ways these five little poles are wired. It's not easy for someone to get into something like this, to get a Uher tape machine from Germany and try to run this in the States. "Oh, what do I do with this cable? Where do I find it? I plugged in a MIDI cable. That doesn't work; it only works on one side." It becomes complicated. There's a self-help group about DIN cables on the subreddit.

LP: That's amazing. What country or territory yields the best stuff? It seems like there's this real, and not just in your work, but it seems like there's this really interesting set of equipment that comes out of the former Soviet bloc or specifically East Germany. Is it just that equipment is foreign to the West, so there's interest in it, or does that area have specifically unique and interesting gear?

Hainbach: They tried to compete with the West, and they copied things from the West, but they were always way behind. That's also due to cultural politics, especially with synthesizers. Synthesizers were not allowed up until 1980 in East Germany. The first synthesizer that came out in East Germany was the Vermona; Bernd Haller worked at Vermona. When he came to Vermont, he already had plans for that in the mid-70s. He could have built it right then, but then the politburo said, "No, no, no, this is against social realism. East German musicians don't need synthesizers."

He said, "Okay, fine," and he kept building instruments with auto company machines and synthesizers for dance musicians who could afford them. They would because there was a booming black market for musicians, and you could make money on the side. They were interested in all this equipment. They tried to buy Western equipment. If they couldn't, they would commission someone like him to build something for them.

So there is always a thing where you have to see that these things were made in spite of a lack of everything, in spite of a lack of microchips. They had to smuggle in microchips, for example, and there was always a lack of that. There were always very weird decisions. There were synthesizers. Who would make this first digital synthesizer for East Germany? Okay, it's the company that makes computers. It's not the people that have been designing instruments forever. They were like, "Oh, what are we going to do? I've got no idea." "Okay, we go to those people." "Why do you have to?" "Because that functionary said we have to make this." They had to make it. It's a very top-down way of how things were made.

When you put these things aside from what was possible in the West to what was possible, what was done in the East is laughable. The technological level is always at least five years behind. But for us now, I think that's often very interesting because it results in unique tones. Often, these synths do not sound the same because they just use whatever parts they have around them. They had to find very creative ways to make a low-pass filter, for example, on the Poly Vox. It's very different from what you could do easily with all these synthesizers on a chip, where you've got one chip that has all the things that you need on it. That's not how they did it there.

It is a bit alien, and that makes it interesting. It is alien to how we are used to things being made. I like to see the human ingenuity in the technicians and designers and how they make things. I appreciate some of these things, their tone and sound. It's very different from anything that you get in the West at that time and now, and that makes it interesting. It's just built differently, and it varies widely in sound.

It also looks different. It feels different. Behind me, there's this big drum machine prototype from Latvia from the last days before the fall of the Soviet Union. It's a Frankenstein instrument. It's an absolute monster. You don't know what this is. They obviously tried to look at drum machines from the West, like the TR-808, which was already 10 years old by that time, and they tried to make something similar, but it had to be better. It has a 24-step sequencer. That's something you can sell to the functionaries. "Oh, it has more steps. Okay, that's good. That's already better than the West. Yes, with 16 steps. Okay." Same thing with the Vermona. Always 32 steps better. "We have one advancement over the West. We got more steps."

But still, it's an absolute monster. At that time, digital drum machines were a thing. Everything sounded very hard and punchy, and all the musicians in the Soviet Union or behind the Iron Curtain didn't want to play these things. They wanted the Western equipment. I saw the ads. They wanted to buy a DX7. They wanted to have all the good Western stuff, and they didn't even want to play Vermona. Even the people who ran Vermona were very unsure if they would take up the brand again because three of these people who made the Vermona brand worked at the original Vermona. At the time, nobody wanted their stuff because it was the thing that they had to play. The musicians had to play this sandy organ. They had to play this synthesizer. They had to play this drum machine. They were very doubtful if that was a good choice. In the end, it was a good choice because, for us here, it's unique. So that was a good choice, in the end, to revive that brand.

LP: It's beautiful from an industrial design point of view. In one of your other videos, you were demoing the Subharcord. I hope I said it right.

Hainbach: Yeah, the Subharcord.

LP: Beautiful. It looks like something that would be on a spaceship in a '50s science fiction movie, but so fun. Just such a cool-looking machine.

Hainbach: Yeah, absolutely. But then again, many of the ideas that are in there are from Western instruments. They said, "Okay, so this is from the Trautonium. We take this, and from this Siemens thing, we take this, and now we make it in a new thing." Then the functionaries said, "Oh, there's no such thing as subharmonics. That's not scientifically proven. Is this in the right of social realism?" Then they did a demo for the functionary, and he said, "Oh, okay, that's good. Then you can make this." Then, the inventor absconded and went over before the wall came to Berlin.

It's so interesting because you have this incredible, amazing experimental instrument. Still, then you have it hampered by a very tiny keyboard, a very tiny, very inflexible, and very bad for playing the keyboard. It's like you have a Ferrari, and then you put in the motor of a… it's not the motor. What would be like the steering wheel now? And then you put it on training wheels. You put it on training wheels. It's like, "I can't drive, but all the power, it's there." It's something different.

LP: Is there a holy grail piece out there that you know exists but you haven't found yet? Is there something you're searching for?

Hainbach: I found one of my holy grails now, a filter bank that was used everywhere, like Urkam in the Polish studios. I found the Brunel and Kier filter bank, and I found one from Urkam. It was thrown away there in the '80s or something. That was one of the holy grails.

Then there are some, I think, somewhere in a museum where there's also Tonto, the big synthesizer that was used in the Stevie Wonder production. I think they have an instrument there that I was really curious to check out, but I forgot the name. I want to travel to Canada to check that out because they also have a Novachord. I've always wanted to play a Novachord.

There are so many things. In the end, right now, I think there are two things in me. One thing is I have all the instruments that I need to make the music that I want to make, so I don't need to play with that or with this or with that. But then I have the ambition to have played with everything so I know I can have informed instruments. What I say is informed. It's not just reading knowledge. It's like informed. I've played with this instrument. I've made music with it. Then I know how it works. It's just a deeper level of understanding.

LP: You can add it to your palette. It will not be in your palette until you have experienced it.

Hainbach: Yeah, and it's the same. It would be so weird to make all these plugins without having deep knowledge about all the different analog hardware. How could I judge, for example, tape echoes if I hadn't worked with a Space Echo? If I had just worked with Dynacords, I could have said, "Okay, so this is how a Dynacord works. This is how a tape echo sounds." But then you are like, "Ah, okay, but the Space Echo, the tape part is interesting, but actually, the input preamp, and if it's an older one, that's the stuff that makes it really interesting, that overdrive and the spring reverb with that. That's what's the sound, that makes the sound of it. That's the secret ingredient. The tape is just there, but the overdrive makes it interesting." All these little things that come from knowledge are something that I really want to see and explore.

I have to think about the holy grails more. Every time I think, "Oh, I'm done now. This is, it seems like there's not so much," another thing pops up. For example, I really would love to play with the real ANS synthesizer, the one in the Soviet Union that you draw on.

LP: Oh, wow.

Hainbach: So there's somebody in London who makes the Oramics machine. I would love to play with that and explore it in the style of Daphne Oram. I would love to work with those things. I need to work with the EMS Synthi 100 at some point. I just need to figure out which studio I want to go to work with, the big one. But there's time.

LP: I'm going to ask you to break it down into simple terms for our audience. Could you talk about what it means to make a plugin? What are you actually doing when you're commissioned to make a plugin?

Hainbach: I'll talk about the process with AudioThing, who I work with. Carlo at AudioThing just asked me after he saw a video on my Soviet Viya recorder, "Hey, that's a nice thing. Shall we make a plugin out of it?" He said, "Yeah, okay, cool, let's do it."

What that involved was me doing measurements upon measurements upon measurements, like throwing everything at this instrument, at this recorder, to see if there's anything we can learn from sweeping, from putting in noise, from putting in little pulses. You try to see all the things that make this machine tick. Then you end up with basically your fingerprint of the machine. Then you should be able to open this in another program, and then it should give you a representation of the thing. That's called convolution. Something like this didn't work because it requires a very pristine, very clean environment. These machines, this Viya recorder, just sounds too dirty. There was just all this noise.

So then we said, "Okay, we need to black-box this. What's actually happening when you record a signal on a wire?" I didn't go into the physical side of it. I went into the listening side of it, and I listened. I thought, "Okay when this input at this frequency hits this level, it happens." How can I replicate that? I basically built a whole patch in my head of things that happen at certain frequencies, when that happens, and then, and then, and then. Then, it becomes a feedback system where everything becomes alive.

I gave Carlo from AudioThing the ideas that I had. I said, "Look, this is when this and this." He said, "Okay." Then he gave me the model that he made from that. Then I got to tweak all the different settings until I couldn't hear a difference anymore between the original and the plugin. That's one of those things. It's a form of figuring these things out, not from the technical standpoint for me, but from the musical standpoint: how does it sound? Why does it sound like that? That's exciting to me.

Then there are other things, such as the glorious idea of modeling a gong amp, which is a resonator made in the 1930s. That resonator is basically a gong with an exciter. You can plug in your guitar, and then, instead of a loudspeaker, a gong will resonate. It sounds absolutely beautiful. It was built by Maurice Martenot. Wonderful, in the 1930s, a very old invention.

So I captured that, captured the impulses, used different microphones, made processing with it, and that sounded really good. But then, to make it alive, we needed to do a bunch of things. I had the idea, "Hey, I like to prepare things. I like to put on cymbals, I like to put in chains, like every experimental drummer at every art gallery show ever. I put on chains." Suddenly, we had a week of work just figuring out how a chain bounces on a gong. It was such fun but also infuriating work because you go into physical modeling, and that single chain—it's two different chains now—took so much time to figure out that it sounds alive.

That's another thing. You have to think about people. Not everybody has the most high-end laptop or computer, and they want to buy it and use it. It's easy to make things that sound incredibly good when you have an incredible amount of processing power. That's not how it works. Then you get very angry customers who say, "Your plugin, just put one on, it's 70% of my…" Okay, yeah, so you need to find a balance between processing power, what you can do there, and sound. Then, of course, you take it further. In digital, you can do unreal things that you can't do with the original. Then, the real fun part starts. That's like figuring out what the next thing can be, what the next thing that this can do that the original couldn't do.

This is like when I do work with AudioThing. Then I also did a plugin called Fluss, which was more generally based on… It's a granular synthesizer. A granular synthesizer takes sounds and, instead of thinking in waves that all sounds are waves or frequencies, well, it's not waves. It's little particles. When you put enough of these particles together, the sound happens. That's the idea behind granular, and it was pioneered by Iannis Xenakis, a Greek composer who was shot in the face by a Sherman tank in the Greek war for independence. That experience really stayed with him, and he tried to figure out ways to put that into music. One of the ways he wanted to put this to music was granular synthesis, to develop sound systems where particles can fly through the air, be at that spot there, go over there, crash, incredible motions of sound, same as you get in the demonstration when the tanks roll in.

I was so fascinated by that idea that I pictured to Bram, with whom I did Fluss, "I want to make something where you have these sounds like an interface," because this is going to be on the iPad, which is the perfect, wonderful interface for letting things fly through space. Then you take these particles of sound, smash them there, and then crash them in this. It was very animated like this. He looked at me like… and I heard nothing for half a year. I thought, "Okay, this is too much. I overreached what this idea is like." Then, after half a year, he came, "Look, I made something." He had taken all these ideas and made them into something that's actually easily playable for people and fun and easy. I was like, "My God, this is fantastic." Then we tweaked onwards. But it all came from this big, "Come on, let's smash things together."

LP: When you communicate with the person programming the plugin, what language are you communicating in? Are you speaking in terms of frequencies? When you mentioned the Soviet wire recorder, and you said you had to listen to it to understand what it was doing, what are you then saying to your partner? Is it resonating at this frequency, and it sounds like it has this type of compression?

Hainbach: One thing that really helps is that I spent a lot of time learning modular. I learned how to build my own synthesizers with just a screwdriver and my wallet by putting all these different little modules in a box and then making patch connections. That helped me think about sound design in a much more open and different way.

So then I can say, "If we put an envelope follower at two kilohertz and that envelope follower triggers a ring modulator that resonates at 300 hertz, then we will get the same effect that the wire recorder does." Then, he sets the parameters. There are, like when you would see the development versions of these things, so many parameters that are now hidden. There are now maybe just one knob that does many things, but many of these things are hidden because they're basically the core of what makes the sound of this instrument. They're not the user variables.

LP: Exactly.

Hainbach: And because that's the sound of the thing. That's the same as when you're cooking the ingredients. At some point, like they mesh so well that you don't know what is that, but you can still see, "Ah, there's potatoes, ah, there's peas," and then there's the sauce. But what is the sauce? The sauce is where the thing comes from; the sauce is the source. It's something that's a multitude of components that you can't tear apart anymore. It just becomes good as a source, as one thing.

LP: I guess the project with the plugins and the virtual instruments seems to me about taking these things that you have found, that you have discovered, that you have repurposed and brought into the modern world, and making them available to all creators. It would seem that could be an endless project, given that there is endless hardware that you've uncovered.

Hainbach: There is. There are so many projects that we are working on in parallel. The next one is going to be an actually free one. It's also… but it's not going to be a particular thing. It's going to be very special. We just had a talk today about what it's going to be. This is something that I've, we've been working on for, like, I think it's almost two years now, one and a half years. It involved a lot of travel. It's one of the biggest things I've worked on so far.

The other purpose is even more educational. It's about a certain technique used in experimental music. It required convincing many people to let us do this. That's the big one for, hopefully, April.

LP: Okay, we'll keep an eye out for that. Talk to me a little bit about your work as a composer, specifically when it comes to scoring. Are you a sit-at-the-piano-with-the-blank-sheet-music-and-write-out-the-notation type composer, or what's your modality? What's your methodology?

Hainbach: I go into the studio, and I start turning things on. Then, I usually start playing. That helps a lot. If we're talking about a movie or theater or something, it's already easy because there is something. There's not a blank sheet. There's already the movie. There's already a task.

It's almost easier than making music on your own because you already have a strong partner there. It's like the movie, and then you need to do something. It just depends on the taste of the directors, what they are looking for, and what works for the film. You have to find that balance. What's theirs, what's yours? Then you have to make strong suggestions that are good and that work and find a way to play with the film, with the vision of the director, and with your own vision for the film.

Often, this involves a lot of talking, hanging out too late in bars, arguing, and thinking. Then, with the movie that just came out on the 15th of February called Schock, I really understood what they wanted. They came here, we worked together, and then we went for food. Then we went into a bar, and at 4:30 or something, I really understood what they wanted.

I went into the studio with very little sleep, and I started recording a big piece for the ending, which was based on a bit of a fugue theme but in the vein of an Ennio Morricone shootout that totally contrasted the scene because the scene is a very documentarily filmed shootout. It's no glorification of violence. It's just very like you would film it, somebody just walking behind. It's almost like a war reporter style.

But then to have the music that completely does the opposite and makes it something like from a Western, from an Italo-Western, that worked so well. That felt so good. Then they were like, "Yes," and I was like, "Yes." But I wouldn't have done that if I hadn't known them because that's where the music starts to tell something that seems to be different from the picture. That's something you need to communicate, where the music takes narration. It does narration, and that's something you have to really communicate because it's not invisible at that point. It becomes big.

LP: I think it's an underappreciated part of the collaborative nature of the film, which is everything around sound design. Watching how audio gets mixed, how sound design gets added, and ultimately how music gets added can really make the picture come alive in a way that's incredibly exciting but so taken for granted by the viewer.

Hainbach: Yeah, it's only noticeable when it's bad. Bad sound design feels jarring. But when you've got good sound design, most people don't notice. But sometimes they do.

In that movie, people notice because there's Ab 18 in Germany. You have to be over the age of 18 to watch it. I don't know what that rating is.

LP: R, restricted.

Hainbach: Rated R, restricted. There are many very violent scenes, and the sound helps to translate the violence. It's also how you say it's doctor's violence sometimes, like someone getting a tooth pulled, and that's shown very clearly. Okay, yes, it's very good. It has a lot of practical effects. It's a genre movie—a film noir. Very good. I'm so happy to work with that.

LP: What other art and media influences you or do you consume? Do you read? Are you interested in film? What else do you take in that you incorporate into your mind?

Hainbach: Oh, lots of things. I try to find lots of things. I read a lot. I read tons. I love reading. I read two things. Often, in the morning and in the evening, I read for pleasure. Sometimes, when I've got extra time in the afternoon, I read more things that can give me more knowledge and help me research.

Then I watch a lot of YouTube. I watch a lot of YouTube because there are many fantastic things that people…. Especially if you're going into the fringy subjects, you can discover so many things. There was a very curious story about the question of why a certain keyboard from the late '90s was so expensive. I went on a research trip and found out that in Peru, there are so many people using it to make music. They were responsible for keeping the prices on these old keyboards high, but they had the whole culture, a whole YouTube culture, about shootouts of that particular sound with that keyboard. It was really interesting to go into.

But then I like to go to shows. I like to go as much as I can, which is a bit hard with two kids and touring myself. I like to watch music, and I like to go to art galleries and museums. That helps a lot. I do watch films, too, but that's, again, another commitment with two kids.

I try to absorb all these things because that makes you grow. But in many things, I'm still drawing from what I learned during my studies. I studied English and musicology, and many of the things that I learned there still help me. I've got a good basis in the theory of music, and that really helps to have that as a foundation.

I consume a lot of instruments. Definitely one of the main things that I consume. Oh, and the best thing is nature. Definitely. It's very typical German of me, but I like just to go out and look at nature, and that helps me. That helps me a lot to calm my mind. Suddenly, ideas just start popping up. Sometimes, when I have to script a video, I script it while jogging because I'm like, "Ah, all the ideas suddenly… it's free, just in the open sky, and ooh, beautiful."

LP: Yeah, the sort of meditative power or contemplative power of a walk or just being… For someone, it's such an interesting contrast with someone who's so deeply technological or technically capable. I would imagine it becomes even more important because you're constantly surrounded by the hum, electricity, energy, and waves.

Hainbach: It's super helpful. I mean, I come from the Black Forest, and I always had the mountains and the forest around me, vineyards, lots of vineyards everywhere, and two castles. I could look… I looked at my childhood home, and there was one castle there and one castle there with ruins. That influenced me a lot.

In Berlin, it's not so much like that. It's a different thing. I'm just lucky that there's the old shut-down Tempelhof airfield. That's where I often go if I want to… It's a bit like going to the sea because there's just a big empty space that you can walk in. It's a treasure for the city.

LP: What is the significance or the closest English approximation to your name?

Hainbach: Hainbach. 'Hain' is a grove of trees, a small grove of trees. And then 'Bach' is a little river. So it's a small grove of trees by a small river. It's my mother's maiden name.

LP: Oh, beautiful. Given all of the things that you do and the avenues that you pursue, how do you self-identify? What are you primarily?

Hainbach: Musician first, and then all the other things. I accept 'YouTube personality' or 'video persona,' which was a fun one. Then software developer, because, ah, that's something. I had to get life insurance because we bought a house, and the life insurance that you have to take for the mortgage was cheaper when I was a software developer than as a musician or composer. So I said, "I'm a software developer now." That saved me six bucks a month.

LP: That's incredible.

Hainbach: I thought I would have assumed composers lived long lives, but no, composers taste the same as musicians. Then they looked at the statistics and said, "Ah, no, not good."

LP: That's an incredible piece of trivia. I love knowing that. One thing I have to say before you go is that the YouTube channel is incredible. The library that is there, first of all, your personality, your video personality definitely comes through, and it radiates the things you talked about, the joy, the curiosity, the wonder with the equipment, and the sounds that come out. It's just that they're beautiful videos to watch and a wealth of information. The material is just, it's so exciting. In a world where I don't need more material to consume, I was like, "Oh, this…" I mean, it makes you want to watch every video. They're so fun and engaging. I just wanted you to know I really enjoy what you're doing.

Hainbach: Oh, thank you very much. Thank you very much. It is a lot of work, especially the editing. Sometimes I'm like, "Oh, no, I don't…" But one thing that I learned, because I started this with a very rigid mindset… I would do two videos every week. That was when I transitioned from just posting music because I had gained like 10,000 subscribers by just posting my music. That was the thing.

Then, so many questions came that I thought, "Okay, I'm just going to start answering these questions on video instead of writing long essays in the comments." Then I said, "Okay, cool. So people like these too. It's horrible to make." I can't watch my early videos because I'm like, "I'm…" This is a video on the Vogue Tech Omnicord. "When you press the button, it's horrible." I'm so stiff, and I don't even look at the camera, right? Because I look at the tiny screen next to it. I don't know where my voice is. Sometimes it's here. I don't know because, "Look, microphone." So then I talk deep, and then my voice is here. It's very… I didn't know. I didn't know what I was even on the camera. It took a long time to find the personality, the video personality.

Then, I did two videos every week. That was good for the growth of the channel because it was at the time when that was especially rewarded, just putting out stuff continuously. But then I realized this pace is unsustainable, completely unsustainable. I need something more chill. Now I worked out I'd rather post less, but more, less constant, but better.

I try to make better videos and not waste anybody's time. I'd rather make the videos just better and post them. What easily makes the videos better is when I enjoy making them. When I'm too tired to go at the camera and talk, then I don't. I did that. I did videos where I was really tired. Then I still, of course, have to do it. Then I realized, no, this is not good. This doesn't work. It doesn't resonate as well because it translates that I'm not an actor. I'm just me.

So then I decided I'm just going to make the videos when I really feel like it. Luckily, that's most of the time. I really enjoy making this. The one thing that I really don't enjoy is that sometimes, now I've got four or five or eight different videos that I'm working on in parallel, and I need to finish. Sometimes I just want to be like, "Ah, what's this box? Let's make this box." Sometimes, I do that versus the next video. It's just that as our camera stops the entire schedule, just make this. That's fun. Oh my God, it's fun making these videos.

LP: It's really interesting what you say there, though, because I do understand that there is this world where there are very successful people, whether it's on YouTube or TikTok or whatever the current platform is, where the algorithm and the platform has its best practices that it's telling you to do, whether it's post twice a week or do something every two hours, whatever it is. There are people who can do that, have mastered that, and are successful as a result. I would consider those people content creators. I don't demean them or look down on them, but they are riding that wave.

But when you have a creative person who is just using the platform to express what they have to say when they have something to say, that's a different form of success. That's something that resonates a little more for me. Not that I can't enjoy viral content or whatever, but there's a difference. There's a difference.

Hainbach: That's very interesting you put it like that. That's actually pretty freeing. Thank you for this. This is a good point. This is actually a good point. One thing that I realized, because when all of this… I mean, I've got many friends that do YouTube videos now because I basically met most of the people that are doing… that are in this space of creating with instruments and electronic music. Everyone is different. Everyone does their own thing. Everybody's their very own person. There's not a, how you say, a competition that's going on. It's just that everybody's so different, but there's still not a lot of experience in how this whole thing goes. Because this thing, being a video personality, is still very new. It's still something that we're still seeing how it is, and it constantly keeps changing.

This year, it felt like it was the time when everybody said, "I'm not going to do this anymore." I think everybody in January was like, "No, I can't do this anymore." I think that's everybody, that's the post-COVID hangover that everybody has, where everybody was like, "Oh my God, everything's blowing up. Everybody's watching. Everybody's at home." Now, not so much anymore because, of course, everybody is busy again. That was a boost that then went down. It was really interesting to see all of that right at the point when I was like, "Ah, I just want to make videos," and I shot two. I was like, "Ah, it's fun. Oh, are you all, you're all leaving? Okay. I'm still here."

LP: Yeah. Well, thank you. Thank you so much. I've enjoyed talking with you, and I look forward to trying to watch the entire library of videos at some point.

Hainbach: Thanks for having me. This was a lovely conversation.

Hainbach

Musician

Based out of Berlin, Germany, electronic music composer and performer Hainbach creates shifting audio landscapes THE WIRE called "One hell of a trip". He has been fascinated with electronic sounds since he discovered the dial on the radio. Never losing his childhood wonder, he still searches for the sounds in between on modular synths, tape and test equipment, making even the unmusical "music". Through his YouTube channel Hainbach brings experimental music techniques and the history of electronic music to a wider audience.